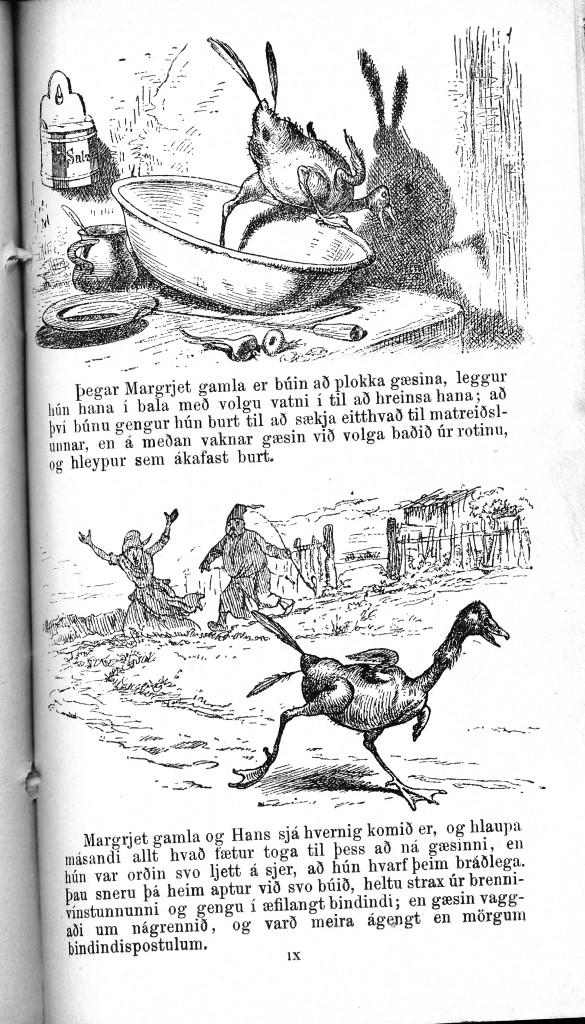

Here are the last two frames of the cartoon that your lang afi and amma were reading in 1892. Who were these people, these ancestors of ours? What did they read, what did they enjoy? Did they grin and say over kaffi, “Did you see the latest cartoon in the Almanak?” Too often when we talk about the people in our past, we quit thinking and feeling and understanding them as people, as people with daily lives, with thoughts, feelings, beliefs. When I see pomp and ceremony “honoring” them, I wonder how much it has to do with them and how much with us? Are we “honoring” them because we think they were important or because it makes us feel important?

I remember my lang amma on my amma’s side of the family; she didn’t die until I was fifteen. She loved to play cards, she liked romance stories, she knew how to laugh in spite of numerous tragedies in her life including the drowning of two of her sons when their sailboat got caught in a storm. With them, three other young people drowned.

I remember my lang afi on my afi’s side of the family.

Neither of them were pretentious, self-important. They both had to work hard all their lives. They made the best lives possible for their children. Are these the people we honor, are these the people we have parades and speeches and ceremonies for or is the flag waving and the speeches and the celebrating for some mythical pioneers, pioneers who never existed, pioneers who were never human, never enjoyed a joke or a romance story or a popular novel?

Here is my rather sad translation of the cut lines below the pictures. I’[m using Zoega’s dictionary published in Reykjavík in 1904. Do you know about Zoega? He was the most famous guide in Iceland in the 1800s. He was a shrewd businessman. But more about him another time. Once again, I’d appreciate anyone helping out by doing a proper translation of the text.

When Old Margrjet finished plucking the goose, she put it in a bowl of warm water to clean it. While Margrjet went off to get something else to cook with the goose, the goose woke up and ran off.

Old Margret and Hans saw the goose and ran after to catch it but they ran out of breath and the goose was so light on her legs that she ran out of sight. They immediately thought of the leaking brennivin and stormed about the village telling people to control their geese and were more aggressive than the people who went about preaching abstinence from liquor.

The humour in this cartoon would be easier to appreciate if I could translate better. As I looked at the pictures and translated, I laughed to myself and thought the goose was a bit like some people I’ve known. They never missed a chance of a drink, never knew when to stop, fell down as if dead and, sometimes, got plucked and, when they sobered up, ran off. As for Old Margrjet and Hans, I’ll leave them to your imagination.

Here are Vidar Hreinsson’s translations. According to this, I didn’t do too badly. Vidar, as most readers will know, is the author of Wakeful Nights, the biography of Stephan G. Stephansson, the poet of the Rocky Mountains. It’s a brilliant book and, I hope was under the Xmas tree of the members of the INL and the readers of this blog.

1. The joy comes to an end. The goose rolls over, dead-drunk and lies as if she was dead. (stjörnu þreifandi is a colloquialism, literally star-fumbling-drunk)

2. Old Margrét has found the goose, thinks she is dead, and tells her husband about the accident. In order to have at least some use from the goose, she intends to have her for dinner, and sits down and plucks her, crying.

3. When old Margrét has plucked the goose, she puts her into a tub with lukewarm water, in order to clean her; after that she walks away to find something for the cooking, but in the meantime, the goose recovers and wakes up in the lukewarm water, and runs away as fast as she can.

4. Old Margrét and Hans see what has happened, and run puffing as fast as they can to get the goose, but she was now so light on foot, that she soon disappeared. Then they returned back home, emptied the keg of brennivín right away, and started a lifelong abstinence; but the goose waddled around in the neighbourhood, and made more progress than many a preacher of abstinence.